This article was originally published on June 4, 2021.

I was 20 years old when I received one of the most unforgettable phone calls of my life. It was my boss, telling me not to come to work. I asked her if something was wrong. She said, “Have you been under a rock all morning? Turn on the TV—our whole country is under attack!”

There I was, a college student looking on in horror as September 11, 2001, unfolded on television. Like so many, my horror turned to sadness, later to rage, and then to numbness mixed with confusion.

On March 19, 2003, I sat in my dorm and wrote in my journal: “It’s official. We have gone to war against Iraq. I feel like crying . . . but for some odd reason, I can’t.”

I was truly lost when it came to our post-9/11 actions in the Middle East. I so badly wanted justice for the families of those lost in the attacks. I wanted safety for our country and not to show up to church and see yet another posterboard in the vestibule full of photos of soldiers killed in combat. I also believed strongly that any action our government took should reflect our values of liberty and justice—and I questioned whether that was happening. But I thought surely with the “adults in charge” . . . I should not have much to worry about.

While I was pondering all this from the comfort of my dorm room, a young man suspected of ties to Al-Qaeda, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, was transferred to an isolation cell at the detention camp in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in late May 2003. He was held without criminal charge and subjected to abusive interrogation, extreme cold and noise, extended sleeplessness, and forced standing and other postures for extended periods. Threats were made against his family, and he suffered sexual and other types of abuse.

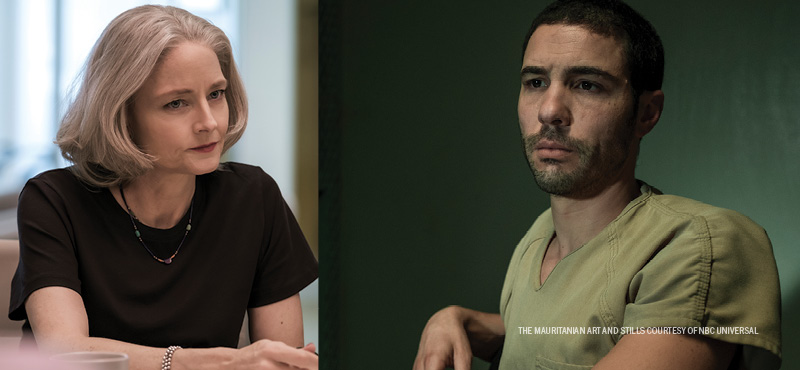

His extraordinary story was documented in his memoir, Guantánamo Diary, and in the recently released film adaptation The Mauritanian, starring Jodie Foster, Tahar Rahim, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Shailene Woodley.

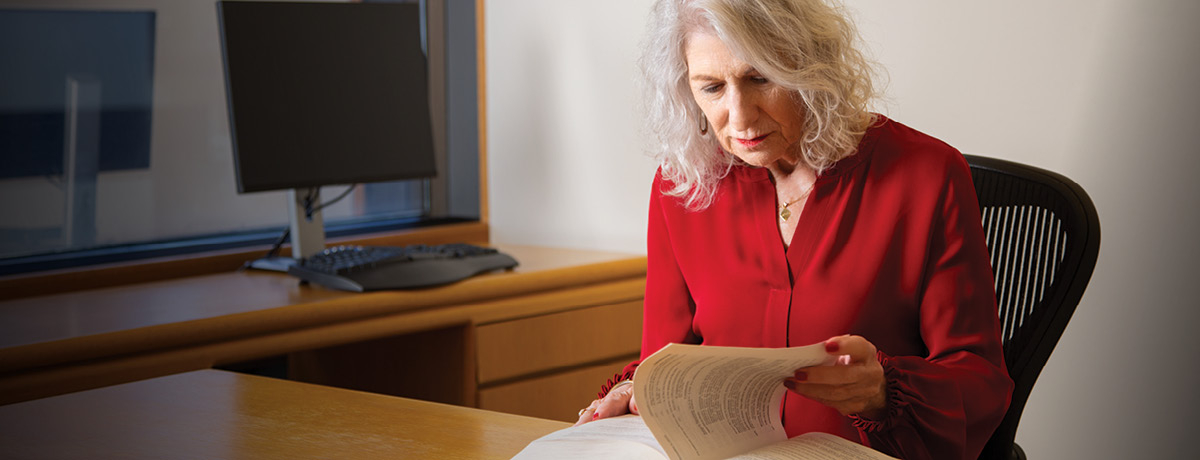

Slahi’s attorney, Nancy Hollander, portrayed by Foster in the film, has been a Best Lawyers–recognized attorney in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for Bet-the-Company Litigation, Criminal Defense: General Practice, and Criminal Defense: White-Collar since 1989. Since 1980, she has been with Freedman Boyd Hollander Goldberg Urias & Ward P.A., devoted to representing individuals and organizations accused of crimes, including those involving national security issues.

I could spend an hour going over the many incredible things she has accomplished. All the recognitions, publications, appearances on Court TV, Oprah, the Today show. The Chelsea Manning case—she was lead counsel on her appeal and her clemency petition. How do you know you’re a rock-star attorney? When you use your expertise and government clearance to help free an innocent man who was locked away and nearly forgotten for 14 years—and Jodie Foster plays you in the movie.

To me, though, what makes Nancy so special is her profound devotion to her clients and to our values of liberty and justice—the values I scribbled about in my journal nearly 20 years ago. Nancy, it turns out, was the “adult in charge.”

I had to meet her . . . and so I did.

Nancy, I was excited to meet you after seeing The Mauritanian. The film brought back memories, particularly my idea of what Guantánamo Bay was supposed to be—a place we needed to send only the most dangerous people. It was supposed to serve some kind of better purpose.

No, no. It was never supposed to serve a better purpose. The Bush administration decided to put people in Cuba on the theory that they would be outside U.S. jurisdiction and not subject to any U.S. treaties, including the Geneva Conventions. And that they would never have lawyers. It was bad to begin with, totally outside the rule of law. It took a series of Supreme Court decisions to make it possible for detainees to file writs of habeas corpus in the federal district court in Washington.

But then Congress said, “They can file, but the government doesn’t have to respond.” Finally, in 2008, the Supreme Court ruled that the government had to respond. Then it responded, but with little evidence. We had to file numerous motions to compel.

You’re representing Slahi, who has already been imprisoned without charge, and meeting nothing but resistance.

It went on until, in 2010, [District] Judge [James] Robertson granted [Slahi’s] habeas petition, ruled that the government did not have sufficient evidence to hold him and ordered him released. The government didn’t need proof beyond a reasonable doubt, only a preponderance. They just needed to tip the scale. Just tip it a little bit. They couldn’t even do that. So we won. But then the government appealed under the Obama administration, which was contrary to [Obama having said] he was going to close Guantánamo.

Slahi had been detained, shipped to Guantánamo Bay, interrogated, abused, and imprisoned for years without trial. Here was a judge who understood the injustice—but his ruling wasn’t enough to allow Slahi to go home. Then what?

The court of appeals remanded it to the district court, and it sat there. Six years later, [Slahi] finally got out through an entirely different process involving six intelligence agencies ruling unanimously that he was not a significant threat to the U.S. or its allies. He got out—but he was innocent and should never have been there. You must remember, there were about 779 people there originally. President Bush released 500. After saying they were the worst of the worst, 500 went home. There are a few people there who probably could be charged with crimes. Not many.

Where does that leave us today?

There are 40 there now—six already cleared for release, one 10 years ago. Why are we holding them? There are about 25 more who we call “forever prisoners.” Well, we don’t have forever prisoners. We don’t have indefinite detention for people who’ve never been charged. If they can’t charge them, they must let them go. Then you’re left with some who have been charged under the military commission. Those cases have to be resolved, but in a way that’s fair and within the rule of law.

My grandfather fought in World War II. What did we do with our prisoners then, and when did things change so drastically?

They were prisoners of war. They were held, they were not to be tortured, not to be interrogated. They were held until the end of the war and then released. So now we have this thing called the War on Terror, and the government says the whole world is a battlefield. It’s absurd—it means they can pick up anyone anywhere. But they’re not being held as prisoners of war. They’ve all been interrogated. Some have been tortured, like Mohamedou was.

It sounds like there’s a loophole because they’re not members of a recognized state. Our government thinks, “You’re just a terrorist, so you’re not going to be held to Geneva Conventions standards.” Is that the case?

No. That may have been what the Bush administration said, but the Supreme Court over and over has said these prisoners are entitled to the protections of the Geneva Conventions and to petition for habeas corpus. But then it gets complicated. Before our appeal was heard, the court of appeals ruled in Washington that the legal standard for what it meant to support AQ was so relaxed that almost anyone would fit it, me included. This ruling made it almost impossible for anyone to win a habeas case. Guantánamo is still a black hole. The War on Terror is made up, “enemy combatants” is made up. These are not prisoners of war. About 15 percent were captured on an actual battlefield. Mohamedou wasn’t. We dropped leaflets—I’ve seen them—over Pakistan and Afghanistan that said, “Turn in a terrorist, get $5,000.” Do you know what $5,000 means to an Afghan farmer? They just turned people in. The whole thing is absurd. It has to end.

If we’re in a situation where we have legitimate reasons for defending our country against foreign enemies, what does justice look like?

Think about this: People were killed, right? So we start a war in Afghanistan. [The 9/11 victims] weren’t killed by Afghans. We start a war in Iraq. They weren’t killed by Iraqis. We know who killed them, and most of them were Saudis, but Saudi Arabia is our big friend. It’s like Alice in Wonderland. We shouldn’t have a War on Terror. Arrest the people who were actually involved in planning 9/11 and try them in a real court.

We shouldn’t have the crime of terrorism. It is always a political crime. Charge people with what they may be guilty of: murder, rape, ethnic cleansing, genocide, espionage. We have all those. We don’t need terrorism, which always becomes a collective crime. You charge someone with murder, you’re looking at that person. You charge someone with terrorism, you start looking at his ethnicity, and then you start looking at others like him. Mohamedou talks about what one of the guards responded when he said, “Why am I here?” [The guard] said, “You’re young, you’re smart, you’re an engineer. You travel, you speak languages. That’s just like the terrorists.” How ridiculous is that?

There were scenes in The Mauritanian that made me ask what I would have done as a defense attorney. On one hand, I’d have a difficult time defending someone I thought might be guilty. On the other, I’d have to consider how I’d feel if I were a defendant. Would I want someone defending me who might be swayed by how everything looks on the surface, or someone who’s got my back regardless? I’d want someone who’s got my back.

Right. And even if those things were all true, even if he were guilty, we would always fight to have the government act fairly, within the rule of law, and not torture him. We would zealously defend him no matter what.

Do you feel like that philosophy came through in the movie?

I hope so. Plus we have Colonel Couch, the prosecutor, who comes to the same conclusion. That was all real. He’s a real person, and he really did say, “I’m not going to do this.” He took another case, but not this one.

Charge people with what they may be guilty of: murder, rape, ethnic cleansing, genocide, espionage. We have all those. We don’t need terrorism."

You also represented Chelsea Manning. Even though President Obama commuted her sentence, it still didn’t sound good, what happened to her. What does that mean for other whistleblowers?

First of all, Obama’s administration prosecuted more whistleblowers than any other, and there’s no good-faith exception to espionage. You have no right to disclose something that should be disclosed, that shouldn’t be classified, that was only classified to protect the government from embarrassment. She got this incredibly long sentence, longer than people who have actually turned over stuff to our enemies. I think Obama realized that, and she’d already served six and a half years. We went on to finish her appeal, but we didn’t think we’d get far because she’d had her sentence commuted. She has not been pardoned. She’s still guilty. She got a dishonorable discharge. She has no rights under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. She doesn’t get free medical care, any of that, but she’s free.

It’s a great outcome for her, considering the circumstances, but then there’s Edward Snowden, who’s in Russia. Obama’s point of view was, “If he just comes back and stands trial, we’ll be good.”

Oh, yeah. Well, we’re not going to be good. Look what he disclosed, violations of the law that should never have happened. And now there’s Assange. Regardless of what you think of Julian Assange, if he gets prosecuted for espionage, there’s not a journalist in this country who’ll feel safe writing about any national-security case.

I’ve been skeptical about whether Snowden did the right thing.

He did the right thing and suffered for it. He did not plan to be in Russia. He was on his way, I think, to Ecuador when the U.S. pulled his passport, and all of a sudden, he was stuck [in Russia]. It’s not like he went to Russia to live there.

He doesn’t really have a chance at a fair trial. That’s the difficult part when it comes to his story.

He can’t leave Russia. He’s stateless. Maybe he’ll get Russian citizenship to protect his child, so that he and his child have the same citizenship. But he did the right thing. I was in a case where we argued that we were being spied on whenever we talked to people in other countries, and we couldn’t protect our client’s privilege in other countries. The Sixth Circuit threw it out because they said we couldn’t prove it. That was before Snowden. He showed that we were correct.

Do you think the Espionage Act is a violation of the First Amendment?

That’s a hard argument to make because the Supreme Court has said it isn’t, but yes, I think it is. That doesn’t mean you can’t raise [the issue] again.

Do you think that’ll ever happen?

I don’t know. I hope Congress eventually passes a law to provide national security whistleblowing as a defense, let’s say, if it describes something that shouldn’t be classified. But the Espionage Act doesn’t cover just classified evidence; it includes what’s called national security information. And who knows what that is? Let me give you an example. Five members of the Taliban were in Guantánamo. Could not be released because it would raise national security concerns. Then [Bowe Bergdahl, the U.S. soldier] who was AWOL, they found him after five years. He had walked away and been captured by the Taliban, and the U.S. wanted him back. He was ultimately court-martialed. So the U.S. traded these guys for him. Suddenly it was OK for them to go—no national security concerns. “Well, it won’t violate national security to release them because we need to release them to get our soldier back.” The concept of national security is too amorphous. And you know who’s negotiating with the Taliban now? These guys. They were never soldiers. They were politicians, so they should never have been picked up in the first place.

This seems like an untapped area of law. There needs to be at least 10,000 of you bringing these cases to light.

It depends on how brave you are. I know things—about my other client, not Slahi—that the world should know about his torture. Am I willing to go to jail for the rest of my life for standing up and saying, “I don’t think this should be classified”? I’m not that brave. But sometimes I think I should be. These are secrets we shouldn’t have. He’s not allowed to discuss his own memories of what happened. He can tell his lawyers, but we can’t discuss them. I can’t even say the names of the countries where he was in the black sites, even though we won a European Court of Human Rights case against two countries where it is assumed he was held. And they’re public opinions. But if you ask me the names of the countries, I’ll tell you, “I can’t answer.”

I won’t ask.

It’s weird sometimes that people who have clearances know less, or can talk about less, than people who don’t have clearances, even about things that are clearly public. Just because it’s public doesn’t mean it’s not classified. It’s hard for people to understand. People have said to me, “Well, there’s a public opinion.” But I can’t attach that public opinion to a pleading without the pleading being classified.

Are there other attorneys who have that level of clearance? Is it hard to get?

Not any easier or harder than [for] anybody else. We go through the same background review. We fill out the SF-86, the FBI talks to our friends. We have to submit our fingerprints.

With your level of clearance, did you face any friction defending a whistleblower? If a friend of mine with clearance had known a whistleblower, I think they’d call into question his clearance.

But he wasn’t defending him. It’s different when you’re defending someone.

Because you have attorney-client privilege.

Right. And because anyone charged with a felony is entitled to have a lawyer represent him or her. But I know people who couldn’t get clearance because of who they’re associated with, right or wrong. The clearance process, and the huge number of people who have clearance, make you wonder whether it’s even meaningful anymore. Other countries have clearances, but they’re different. I had a client in Ireland, and the informant was American. He was run by the FBI and MI-5—the British FBI, is really what they are—because they didn’t trust the Irish cops. By the time this stuff got to me, it had all been declassified. But then we discovered he was working with some journalists to write a memoir, and we wanted those documents. So we got a court in Chicago to say we could have them. And then the U.S. government said, “We want them first.” Which turned out to be great, because they had to listen to these hard-to-understand tapes, type them up, and give them back to us. They found one name that they didn’t clear. We’re talking about a thousand pages.

It turned out great: “Oh, good. Thank you for doing that for us.” And we all agreed to maintain confidentiality of the material in case he really did want to write something. But the government sometimes steps into other cases and says, “We have an interest.” It’s a murky area. Ali Soufan, the FBI agent, wrote a book. The FBI cleared it. Then it went to the CIA and they redacted it. It’s now been declassified. And they redacted it in such a silly way that it made no sense if you were reading the book. I have no idea who made the decisions in Mohamedou’s book. We had no way of knowing. All I know is, all those intelligence agencies, six of them, got together and unanimously decided he was not a significant threat to the U.S. or its allies. That’s all that matters to me.

But we still have people locked up in Guantánamo, and you’re still working to get them out.

We’re hoping this movie will get Guantánamo back into the conversation. Couch is not the only prosecutor. There were five others who walked away and said, “We can’t prosecute these cases.” But [another of my clients is] accused of being the mastermind behind the [attack on the] USS Cole, a ship that was blown up [in October 2000] in the port in Yemen, and 17 sailors died. Several others were supposedly the “mastermind” before my client. Originally Bush said, “Oh, we caught the mastermind.” There were two others after that. And now my client’s the, quote, “mastermind” of the Cole. We have Navy officers defending him, and they take it very seriously.

We’re hoping this movie will get Guantánamo back into the conversation."

Who’s watching Guantánamo now? How do we know torture is not still happening?

It’s not happening. We do know that.

We do?

Because now everybody who wants one has a lawyer. There are some people who don’t want lawyers. But [torture] is not happening. Except solitary confinement is itself torture and holding people for 15 years who have never been charged is a kind of torture. The torture that happened to Mohamedou in the movie—it was much worse, and all of that is real. Every bit has been corroborated by U.S. sources. They let his book get published with all the torture because it had all been confirmed.

Best Lawyers is a business publication. Is there anything the business community can do?

Interestingly, Mohamedou and I spoke twice to a Muslim business group called the Concordia Forum and I spoke to a large business organization in Europe. I think businesspeople want to know what’s going on in the government, and it’s important that we have a free press. There are people charged with crimes they didn’t commit, and they want to have a lawyer and have the government operate fairly. Whether it’s in federal court or the military courts, they want a lawyer who will get the information they need to defend their case.

[When I was a kid,] there was this club, and men took their clients and employees. Women couldn’t join, and my mother said, “I have to join.” She fought for it, and she was the first woman [admitted]. She was vice president of a big company. My mother was the boss. My father was a small businessman, but it was my mother who made money and had a lot of employees. So I understand the business community pretty well.

To wrap up: I’ve seen you give advice, especially to women, to “be yourself.” What does that mean now? I’m an older Millennial. I grew up with the notion that you don’t have to be a certain way. You don’t have to wear lipstick. Just be you.

To me it means to find your own voice. You can have mentors but be you, not them. Wear makeup, or not depending on who you are and what makes you comfortable—what is your voice.

Do you feel like your philosophy about being true to yourself and standing on principle came from your mother?

Absolutely. She gave me a copy of [Henrik] Ibsen’s A Doll’s House to read when I was 12. I took it to school, and the librarian said I couldn’t read it because I was not old enough to read it. My mother said, “Just read it at home. It’ll make you a feminist.” She was a feminist, and she wore lipstick. Maybe because I grew up in Dallas—we wore lipstick and high heels in high school. That’s who she was, but she was a top businessperson in a man’s world.

It’s amazing how we take these values from our parents. It just reinforces how right they are. Even though there were moments I didn’t want my mom to be right.

And she probably was.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If you’re looking for legal guidance on any matter, use the Best Lawyers Find a Lawyer tool to connect with experienced lawyers ready to assist.